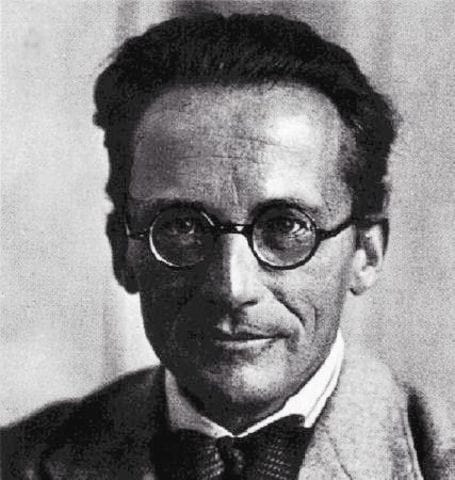

Erwin Schrödinger, the architect of wave mechanics and a cornerstone of quantum theory, is celebrated for his scientific brilliance—most famously for the Schrödinger Equation and the thought experiment known as “Schrödinger’s Cat.” Yet, beyond the laboratory, his intellectual journey ventured deep into philosophy, where he found profound resonance with Vedanta, the ancient Indian metaphysical tradition rooted in the Upanishads. This influence, vividly articulated in his 1949 book My View of the World, reveals a scientist who saw beyond the material, embracing a unity of consciousness that echoed Vedantic principles. Far from a mere curiosity, Schrödinger’s engagement with Vedanta shaped his worldview, offering a lens through which he reconciled the mysteries of quantum physics with the nature of existence itself.

Vedanta Meets Quantum: A Convergence of Thought

Vedanta, derived from the Sanskrit “Veda-anta” (the end or culmination of the Vedas), posits a non-dualistic (Advaita) reality where the individual self (Atman) and the universal consciousness (Brahman) are fundamentally one. This philosophy captivated Schrödinger during a period of intellectual ferment in the early 20th century, when Western thinkers were increasingly exposed to Eastern ideas through translations of texts like the Upanishads and the works of philosophers like Schopenhauer, who himself drew from Indian thought.

In My View of the World, Schrödinger explicitly acknowledges this influence. In the essay “Seek for the Road,” he writes: “The plurality that we perceive is only an appearance; it is not real. Vedantic philosophy… has sought to clarify it by a number of analogies, one of the most attractive being the many-faceted crystal which, while showing hundreds of little pictures of what is in reality a single existent object, does not really multiply that object” (p. 21). This mirrors the Advaita Vedanta concept of Maya—the illusion of multiplicity masking an underlying unity—a notion Schrödinger found strikingly analogous to quantum mechanics’ wave-particle duality and the observer-dependent nature of reality.

Schrödinger’s fascination began in the 1920s, during his formative years as a physicist. Historical accounts suggest he encountered Vedanta through German translations of the Upanishads and discussions with contemporaries like Heinrich Zimmer, a scholar of Indian philosophy. By the time he penned “Seek for the Road” in 1925, shortly before his breakthrough in quantum theory, he was already grappling with questions of consciousness and reality that Western science alone couldn’t answer. Vedanta offered a framework: the idea that the perceived world is a projection of a singular consciousness aligned with his emerging view of the wave function as a descriptor of potentiality rather than a fixed material state.

Consciousness as Unity: Schrödinger’s Vedantic Echo

In My View of the World, Schrödinger repeatedly returns to the unity of consciousness, a hallmark of Advaita Vedanta. He challenges the Western assumption of individual, separate minds, asserting in “What Is Real?” that “the total number of minds in the universe is one. In fact, consciousness is a singularity… the overall number of minds is just one” (p. 87). This radical claim echoes the Upanishadic teaching that “Tat Tvam Asi” (“Thou art That”)—the individual self is indistinguishable from the universal Brahman.

This perspective wasn’t a late-life musing but a thread woven through his career. In a 1956 lecture, he remarked, “I venture to call [this] the most important thing I have ever understood,” crediting Vedanta for illuminating the limitations of materialist science (quoted in Walter Moore’s biography, Schrödinger: Life and Thought). His quantum work, where observation collapses the wave function into a definite state, parallels Vedanta’s idea that perception shapes the illusory world of Maya. For Schrödinger, the observer wasn’t merely a passive recorder but an integral part of reality—a concept resonant with the Vedantic view that consciousness underlies all phenomena.

In My View of the World, he uses a metaphor from the Chandogya Upanishad: “As the rivers flowing east and west merge in the sea and become one with it, forgetting they were ever separate rivers, so all creatures lose their separateness when they merge at last into pure Being” (p. 23, paraphrased). This imagery underscores his rejection of atomistic individualism, aligning his scientific intuition with Vedanta’s holistic vision.

Influence on Quantum Philosophy

Schrödinger’s Vedantic leanings weren’t just philosophical musings—they informed his interpretation of quantum mechanics. Unlike Niels Bohr’s Copenhagen Interpretation, which emphasized empirical measurement over metaphysical speculation, Schrödinger resisted reducing reality to probabilities. He saw the wave function as a real, continuous entity—a “smear of possibility” across space—mirroring Vedanta’s seamless Brahman rather than discrete particles. In “Seek for the Road,” he critiques the “naive realism” of classical physics, suggesting “the external world is a construct of our consciousness” (p. 19), a view that dovetails with Vedanta’s assertion that the material world is a projection of the mind.

This influence set him apart from peers like Heisenberg, who embraced uncertainty without metaphysical grounding. Schrödinger’s discomfort with the probabilistic collapse of the wave function—famously dramatized in his cat paradox—may reflect a Vedantic aversion to fragmenting the unity of existence into random outcomes. His friend and biographer Moore notes that Schrödinger kept a copy of the Bhagavad Gita on his desk, suggesting a daily engagement with these ideas as he wrestled with quantum theory’s implications.

A Personal and Intellectual Synthesis

Schrödinger’s personal life also hints at Vedanta’s impact. Living unconventionally—often in exile, as during his time in Dublin after fleeing Nazi Austria—he embraced a contemplative existence that mirrored the ascetic detachment of Vedantic sages. In My View of the World, he reflects on detachment from material pursuits, writing, “What is it that we really want? Not things, but the meaning behind them” (p. 35), echoing the Gita’s call to transcend worldly attachments.

His synthesis of Vedanta and science wasn’t without critique. Some contemporaries dismissed it as esoteric, arguing it strayed from empirical rigor. Yet, Schrödinger saw no contradiction: “Science is only a means to an end, and that end is to understand the nature of the self and the world” (p. 63). For him, Vedanta provided a philosophical anchor where Western dualism—mind versus matter, self versus other—fell short.

Legacy and Reflection

Schrödinger’s Vedantic influence, crystallized in My View of the World, left a subtle but enduring mark. It prefigured later dialogues between quantum physics and Eastern thought, as seen in works like Fritjof Capra’s The Tao of Physics. Today, as physicists grapple with consciousness’s role in quantum measurement (e.g., the observer effect), Schrödinger’s Vedantic lens feels prescient.

The article’s reliance on My View of the World—written across decades—shows how Vedanta wasn’t a fleeting interest but a lifelong companion. From the unity of consciousness to the illusion of multiplicity, Schrödinger found in Vedanta a mirror for quantum reality, proving that even a scientist of his caliber could look East to illuminate the West’s greatest mysteries.